A CONSCIENTIOUS ASS(良心的なロバ)

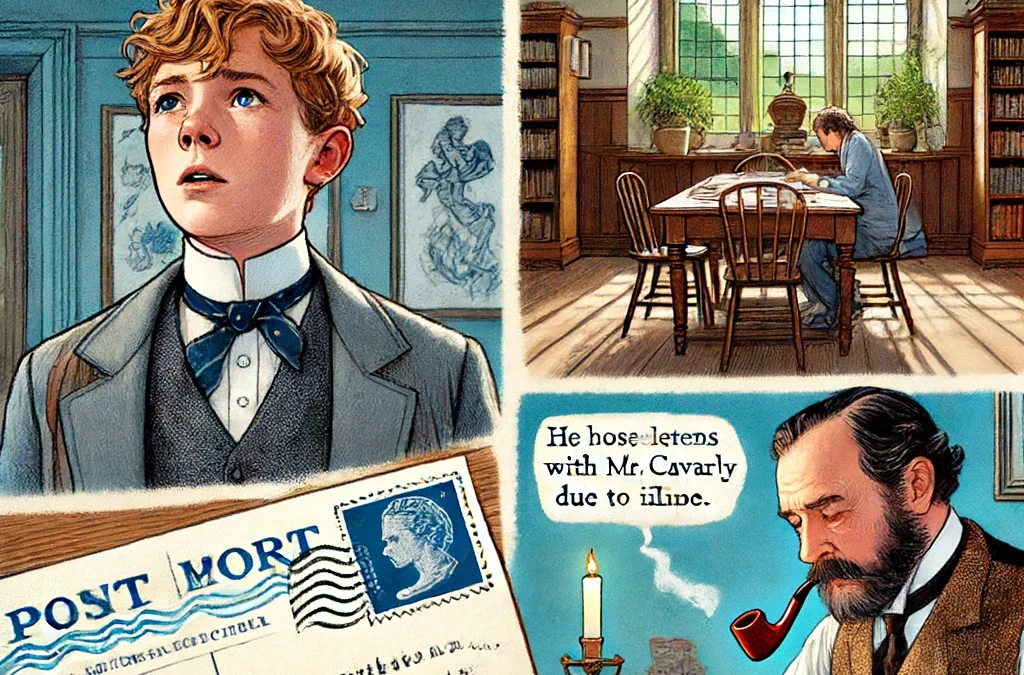

Pocket Upton had come down late and panting, in spite of his daily exemption from first school, and the postcard on his plate had taken away his remaining modicum of breath. He could have wept over it in open hall, and would probably have done so in the subsequent seclusion of his own study, had not an obvious way out of his difficulty been bothering him by that time almost as much as the difficulty itself. For it was not a very honest way, and the unfortunate Pocket had been called “a conscientious ass” by some of the nicest fellows in his house. Perhaps he deserved the epithet for going even as straight as he did to his house-master, who was discovered correcting proses with a blue pencil and a briar pipe.

ポケット・アプトンは、毎日午前中の授業が免除されているにもかかわらず、遅れて息を切らして降りてきた。そして、彼の皿の上にあった絵葉書は、彼の残りのわずかな息を奪った。彼は広間で声を上げて泣くこともできただろうし、その後自習室に閉じこもって泣いただろう。しかし、その頃には、彼の困難から抜け出す明白な方法が、困難そのものと同じくらい彼を悩ませていた。なぜなら、それはあまり正直な方法ではなく、不幸なポケットは、彼の寮のとても素敵な仲間たちから「良心的なロバ」と呼ばれていたからだ。おそらく、彼は寮監のところへまっすぐに行ったことで、そのあだ名をつけられても仕方がなかったのだろう。寮監は青い鉛筆とブライヤーパイプで作文を添削しているところだった。

“Please, sir, Mr. Coverley can’t have me, sir. He’s got a case of chicken-pox, sir.”

「先生、カバリー先生は僕を預かれません。水疱瘡にかかっているんです。」

The boy produced the actual intimation in a few strokes of an honoured but laconic pen. The man poised his pencil and puffed his pipe.

少年は、尊敬されているが簡潔なペンで、実際に通知されたことを数回の筆致で示した。男は鉛筆を構え、パイプを吹かした。

“Then you must come back to-night, and I’m just as glad. It’s all nonsense your staying the night whenever you go up to see that doctor of yours.”

「それなら、君は今夜戻って来なければならない。それはそれで構わない。君がその医者さんに会いに行くたびに泊まるのは、全く馬鹿げている。」

“He makes a great point of it, sir. He likes to try some fresh stuff on me, and then see what sort of night I have.”

「先生はそれをとても重要視しています。新しい薬を試してみて、どんな夜を過ごすか見てみたいんだそうです。」

“You could go up again to-morrow.”

「明日また行けばいいじゃないか。」

“Of course I could, sir,” replied Pocket Upton, with a delicate emphasis on his penultimate. At the moment he was perhaps neither so acutely conscientious nor such an ass as his critics considered him.

「もちろん、そうすることもできますが」とポケット・アプトンは、最後から2番目の言葉に微妙な強調を置いて答えた。その瞬間、彼は批評家たちが考えるほど、鋭い良心を持っていたわけでも、ロバだったわけでもないのかもしれない。

“What else do you propose?” inquired Mr. Spearman.

「他に何か提案はあるのか?」スピアマン氏は尋ねた。

“Well, sir, I have plenty of other friends in town, sir. Either the Knaggses or Miss Harbottle would put me up in a minute, sir.”

「ええと、先生、私には他にもたくさん友達がいます。ナッグス家かミス・ハーボトルのどちらかが、すぐに私を泊めてくれるでしょう。」

“Who are the Knaggses?”

「ナッグス家とは?」

“The boys were with me at Mr. Coverley’s, sir; they go to Westminster now. One of them stayed with us last holidays. They live in St. John’s Wood Park.”

「カバリー先生のところにいた男の子たちです。今はウェストミンスターに行っています。そのうちの一人は、この前の休みにうちに泊まりました。彼らはセント・ジョンズ・ウッド・パークに住んでいます。」

“And the lady you mentioned?”

「で、あなたが言及した女性は?」

“Miss Harbottle, sir, an old friend of my mother’s; it was through her I went to Mr. Coverley’s, and I’ve often stayed there. She’s in the Wellington Road, sir, quite close to Lord’s.”

「ハーボトルさんです、先生の古い友人です。彼女を通して私はカバリー先生のところに行き、私はよくそこに泊まりました。彼女はウェリントンロードにいます、先生のすぐ近くです。」

Mr. Spearman smiled at the gratuitous explanation of an eagerness that other lads might have taken more trouble to conceal. But there was no guile in any Upton; in that one respect the third and last of them resembled the great twin brethren of whom he had been prematurely voted a “pocket edition” on his arrival in the school. He had few of their other merits, though he took a morbid interest in the games they played by light of nature, as well as in things both beyond and beneath his brothers and the average boy. You cannot sit up half your nights with asthma and be an average boy.

スピアマン氏は、他の少年たちが隠そうとする熱意を、無償で説明することに微笑んだ。しかし、アプトン家には悪意はなかった。その点では、3人目の末っ子は、彼が学校に到着したときに「ポケット版」と prematurely 投票された偉大な双子の兄弟に似ていた。彼は他の兄弟たちの長所はほとんど持っていなかったが、兄弟たちや平均的な少年を超えたもの、劣ったものの両方に対して、病的な興味を持っていた。喘息で夜更かしをしていては、平均的な少年にはなれない。

This was obvious even to Mr. Spearman, who was an average man. He had never disguised his own disappointment in the youngest Upton, but had often made him the butt of outspoken and disastrous comparisons. Yet in his softer moments he had some sympathy with the failure of an otherwise worthy family; this fine June morning he seemed even to understand the joy of a jaunt to London for a boy who was getting very little out of his school life. He made a note of the two names and addresses.

これは、平均的な男であるスピアマン氏にも明らかだった。彼は末っ子のアプトンに失望したことを隠したことはなかったが、しばしば彼を率直で悲惨な比較の対象にしていた。しかし、穏やかな時には、彼は他の点では立派な家族の失敗に同情した。この6月の晴れた朝、彼は学校生活からほとんど何も得ていない少年にとって、ロンドンへの小旅行がどれほどの喜びであるかを理解しているようだった。彼は2つの名前と住所をメモした。

“You’re quite sure they’ll put you up, are you?” “Absolutely certain, sir.”

「彼らが君を泊めてくれると確信しているのか?」

「絶対に大丈夫です、先生。」

“But you’ll come straight back if they can’t?”

「でも、もしダメだったら、すぐに戻ってくるんだろうね?」

“Rather, sir!”

「もちろんです、先生!」

“Then run away, and don’t miss your train.”

「それなら、走って行きなさい。電車に乗り遅れないように。」

Pocket interpreted the first part of the injunction so literally as to arrive very breathless in his study. That diminutive cell was garnished with more ambitious pictures than the generality of its order; but the best of them was framed in the ivy round the lattice window, and its foreground was the nasturtiums in the flower-box. Pocket glanced down into the quad, where the fellows were preparing construes for second school in sunlit groups on garden seats. At that moment the bell began. And by the time Pocket had changed his black tie for a green one with red spots, in which he had come back after the Easter holidays, the bell had stopped and the quad was empty; before it filled again he would be up in town and on his way to Welbeck Street in a hansom.

ポケットは最初の指示を文字通りに解釈し、息を切らして自習室に到着した。その小部屋は、一般のものよりも意欲的な絵で飾られていたが、その中でも最高のものは格子窓の周りのツタに囲まれ、その前景は花壇のキンレンカだった。ポケットは四角の中庭を見下ろした。そこでは、仲間たちが日当たりの良い庭のベンチで、2回目の授業のための予習をしていた。その瞬間、ベルが鳴り始めた。そして、ポケットが黒いネクタイを緑色の赤い斑点のついたネクタイ(イースター休暇後に戻ってきたときに着ていたもの)に変える頃には、ベルは鳴り止み、四角の中庭は空っぽになっていた。再び人が集まる前に、彼は町に出て、ハンサム車でウェルベック・ストリートに向かっていた。