※カラフル対訳で紹介している作品はすべてパブリックドメインです。

このサイトで使われている作品のすべては著作権の切れた名作などの全文を電子化して、インターネット上で公開しているProject Gutenberg(プロジェクト・グーテンベルク)、LibriVox(リブリヴォックス、朗読図書館)の作品を出典としています。

翻訳者:中務秀典

I was now beginning to grow handsome; my coat had grown fine and soft, and was bright black.

僕は今、美しく[ハンサムに]成長し始めていた。毛並みは美しく柔らかくなり、真っ黒に輝いていた。

I had one white foot and a pretty white star on my forehead.

一本の足が白く、額にはきれいな白い星があった。

I was thought very handsome; my master would not sell me till I was four years old;

僕はとても美しい馬だと思われていた。ご主人様は、4歳になるまで、僕を売ろうとしなかった。

he said lads ought not to work like men, and colts ought not to work like horses till they were quite grown up.

彼は、少年[若者]は大人のように働くべきではないし、仔馬は完全に成長するまで、成馬のように働くべきではないと言っていた。

When I was four years old Squire Gordon came to look at me.

4歳の時、大地主のゴードンさんが僕を見に来た。

He examined my eyes, my mouth, and my legs; he felt them all down; and then I had to walk and trot and gallop before him.

彼は僕の目、口、足すべてを触って検査した。僕は彼の前で歩いたり、速足したり、全速力で走【る】ったりしなければならなかった。

He seemed to like me, and said, “When he has been well broken in he will do very well.”

彼は僕のことを気に入ってくれたようで、「しっかりと調教すれば、活躍してくれるだろう 」と言った。

My master said he would break me in himself, as he should not like me to be frightened or hurt, and he lost no time about it, for the next day he began.

ご主人様は、僕が怖がったり傷ついたりしないように、僕を自分で調教すると言った。ご主人様は時を移さず[さっそく]次の日から調教を始めた。

Every one may not know what breaking in is, therefore I will describe it.

みなさんの中には、調教とはどういったものかを知らない人もいるかもしれませんから[それゆえ]、説明してみます。

It means to teach a horse to wear a saddle and bridle, and to carry on his back a man, woman or child; to go just the way they wish, and to go quietly.

それは、馬に鞍や頭絡 を身につけ、男や女や子どもを背負うこと、乗り手の思い通りに走ったり、静かに歩いたりすることを教えることを意味する。

を身につけ、男や女や子どもを背負うこと、乗り手の思い通りに走ったり、静かに歩いたりすることを教えることを意味する。

Besides this he has to learn to wear a collar, a crupper, and a breeching, and to stand still while they are put on;

これに加えて、ホースカラー[はも]、 尻がい、尻帯

尻がい、尻帯 を身につけ、それらをつけ【る】ている間はじっと立っていなければならない。

を身につけ、それらをつけ【る】ている間はじっと立っていなければならない。

then to have a cart or a chaise fixed behind, so that he cannot walk or trot without dragging it after him;

それから荷車か二輪馬車を後ろにつける。荷車か二輪馬車を引かずには歩いたり駆けたりしないようにするために。

and he must go fast or slow, just as his driver wishes.

それから、御者が望む通りに、速くも遅くも走らなければなりません。

He must never start at what he sees, nor speak to other horses, nor bite, nor kick, nor have any will of his own;

何を見ても驚いて[ビクッと動く]はいけないし、ほかの馬に向かって話しかけてもいけない。噛みついてもいけないし、蹴ってもいけない。自分勝手なことをしては[自分の意思を持っては]いけない。

but always do his master’s will, even though he may be very tired or hungry;

疲れていても 腹が減っていてもご主人様の意志に従うこと。

but the worst of all is, when his harness is once on, he may neither jump for joy nor lie down for weariness.

しかしいちばん辛い[最悪な]のは、一度馬具をつけてしまうと、うれしいからと飛び跳ねたり、疲れのために横になることができないことだ。[~も~もない]

So you see this breaking in is a great thing.

だから、この調教がかなり大変なこと、ということが分かってもらえるだろう。

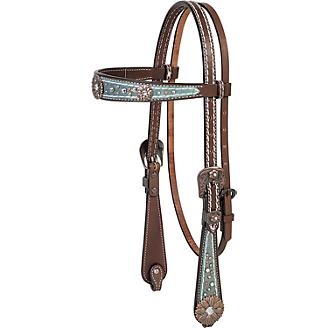

I had of course long been used to a halter and a headstall, and to be led about in the fields and lanes quietly, but now I was to have a bit and bridle;

もちろん僕は端綱 とヘッドストール[おもがい]

とヘッドストール[おもがい] には長い間慣れていて、野原や小道を静かに引き回【す】されていたが、今度ははみ[馬の口にかませて,その両端に手綱をつける環がついている]と手綱をつけることになり、

には長い間慣れていて、野原や小道を静かに引き回【す】されていたが、今度ははみ[馬の口にかませて,その両端に手綱をつける環がついている]と手綱をつけることになり、

my master gave me some oats as usual, and after a good deal of coaxing he got the bit into my mouth, and the bridle fixed, but it was a nasty thing!

ご主人様はいつものようにオート麦をくれて、何度もなだめすかしたあげく、私の口にはみを噛ませ、手綱をつけた。それは、ひどく不快なものだった。

Those who have never had a bit in their mouths cannot think how bad it feels;

口の中にはみ を入れたことのない人には、それがどれほど気持ちの悪いものか想像もつかないでしょう。

を入れたことのない人には、それがどれほど気持ちの悪いものか想像もつかないでしょう。

a great piece of cold hard steel as thick as a man’s finger to be pushed into one’s mouth,

人の指ほどの太さの冷たく硬い鋼鉄の棒[塊]を、口の中に押し込まれ、

between one’s teeth, and over one’s tongue, with the ends coming out at the corner of your mouth,

歯と歯の間、舌の上(に押し込まれ)、両端は口の端からはみ出して、

and held fast there by straps over your head, under your throat, round your nose, and under your chin;

そして頭の上から喉の下へ、鼻をまわってあごの下へと革ひもでしっかりと[固く]固定される。

so that no way in the world can you get rid of the nasty hard thing;

だから、どんなことをしても、この厄介な[胸が悪くなるほどいやな]硬いものを外す[取り除く]ことはできないのです。

it is very bad! yes, very bad! at least I thought so;

それはとても不快です!ええ、とても不快です! 少なくとも僕はそう思っていたんですが、

but I knew my mother always wore one when she went out, and all horses did when they were grown up;

でも、ママが出かけるときには必ずつけていたし、馬はみんな大人になるとつけていました。

and so, what with the nice oats, and what with my master’s pats, kind words, and gentle ways, I got to wear my bit and bridle.

そういわけで、僕も、上等のオート麦[燕麦]や、ご主人様がやさしく撫でることや、優しい言葉、優しいやり方などにつられ、僕もはみと手綱を身につけることになりました。

Next came the saddle, but that was not half so bad;

次は鞍でしたが、それは、(はみや手綱の)半分も嫌ではなかった。

my master put it on my back very gently, while old Daniel held my head;

ご主人様は、ダニエル爺さんが僕の頭を押さえている間、とても優しく背中に鞍を乗せてくれた。

he then made the girths fast under my body, patting and talking to me all the time;

それから、ダニエル爺さんは、その間中ずっと、なでたり[軽くたたく]話しかけたりしながら、僕の体の下で胴回り[馬などの荷や鞍をしばる帯]をしっかりと締めた。

then I had a few oats, then a little leading about; and this he did every day till I began to look for the oats and the saddle.

それから、僕は少しオート麦[燕麦]を食べて、しばらく引き回された。僕がオート麦と鞍を待つ[を期待する・を探す]ようになるまで、彼は毎日これを続けた。

At length, one morning, my master got on my back and rode me round the meadow on the soft grass.

とうとうある朝、私の主人は私の背中に乗って、柔らかい草の上の牧草地を乗り回したた。

It certainly did feel queer;

それは、たしかに妙な感じだった。

but I must say I felt rather proud to carry my master, and as he continued to ride me a little every day I soon became accustomed to it.

しかし、僕はご主人様を乗せて回ることを幾分誇りに思っていたし、ご主人様が毎日少しずつ乗り続けてくれるので、僕はすぐに慣れた。

The next unpleasant business was putting on the iron shoes; that too was very hard at first.

次に嫌な[不愉快な]こと[仕事]だったのは、鉄の靴を履くことだった。あれも最初は大変だった。

My master went with me to the smith’s[鍛冶屋・金属細工師] forge[鍛冶場], to see that I was not hurt or got any fright.

ご主人様は、僕が怪我をしたり、怖がったりしないように、一緒に鍛冶場に行ってくれた。

The blacksmith took my feet in his hand, one after the other, and cut away some of the hoof.

鍛冶屋は僕の足を次々と手に取り、蹄の一部を切り取った。

It did not pain me, so I stood still on three legs till he had done them all.

痛くはなかったので、彼が全部やってくれるまで3本足でじっとしていました。

Then he took a piece of iron the shape of my foot, and clapped it on,

それから、彼は僕の蹄[足]の形をした鉄の切れ端を手に取って、それをカチッと打ちつけ、

and drove some nails through the shoe quite into my hoof, so that the shoe was firmly on.

蹄鉄[靴]の上から完全に蹄にまで通るような、くぎを何本か打ち込み、蹄鉄はしっかりとくっついた。

My feet felt very stiff and heavy, but in time I got used to it.

足がとてもこわばって[硬直した]重く感じたが、そのうち[やがて]慣れた。

And now having got so far, my master went on to break me to harness; there were more new things to wear.

さて、ここまで来たので、主人は私を馬具に慣らす(訓練)に移った。[さらに進む] まだ新しくつけるものがあったのだ。

First, a stiff heavy collar just on my neck, and a bridle with great side-pieces against my eyes called blinkers,

まず、私の首には硬くて重いはも[馬の首かせ]、そして視界を遮る大きな側面の(視界を制限する)馬具[馬勒]、それはブリンカー[遮眼革]と呼ばれるもので、

and blinkers indeed they were, for I could not see on either side, but only straight in front of me;

ブリンカーは確かに目隠し革[ブリンカー]で、僕は側面のどちらも見ることができず、真っ直ぐ前にしか見えなかった。

next, there was a small saddle with a nasty stiff strap that went right under my tail; that was the crupper.

次に、僕の尻尾のすぐ下に、気持ちの悪い、固い革ひものついた小さな鞍があった。それはしりがいという。

I hated the crupper; to have my long tail doubled up and poked through that strap was almost as bad as the bit.

僕はしりがいが大嫌いだった。長い尻尾を折り曲げられて、革ひもを突っ込まれるのは、はみと同じくらい最悪だった。

I never felt more like kicking, but of course I could not kick such a good master,

このときほど、蹴っとばしたいと思ったことはありません。もちろんこれほど親切なご主人様を蹴ることはできず、

and so in time I got used to everything, and could do my work as well as my mother.

やがて僕は何もかもに慣れ、ママと同じように仕事ができるようになった。

I must not forget to mention one part of my training, which I have always considered a very great advantage.

僕の調教の中で、僕がいつも大変良かったと思う、言い忘れてはならないことがある。

My master sent me for a fortnight to a neighboring farmer’s, who had a meadow which was skirted on one side by the railway.

ご主人様は僕を二週間ほど隣の農家に送ったのだが、その農家には鉄道(の線路)で片側が囲われた牧草地があった。

Here were some sheep and cows, and I was turned in among them.

ここには羊や牛がいて、僕はそのなかに入れられた。

I shall never forget the first train that ran by.

僕は、初めて通り過ぎた汽車のことは決して忘れないだろう。

I was feeding quietly near the pales which separated the meadow from the railway,

線路と草地を隔てている柵[境界]の近くで静かに(草を)食べていたとき、

when I heard a strange sound at a distance, and before I knew whence it came—

遠くから奇妙な音が聞こえ、その音がどこからきているのか分からないうちに、

with a rush and a clatter, and a puffing out of smoke—

それは煙を吐きながら、ガタガタという音を立てて突進してきて、

a long black train of something flew by, and was gone almost before I could draw my breath.

何か黒くて長いつながり[列車]が飛んできて、息をつく間もなく消えてしまった。

I turned and galloped to the further side of the meadow as fast as I could go, and there I stood snorting with astonishment and fear.

ぼくは向きを変え、牧草地の向こう側まで全速力で駆けていった。そこで、ぼくは驚きと恐怖で鼻を鳴らして立っていた。

In the course of the day many other trains went by, some more slowly;

その日のうちに、ほかの汽車もたくさん通り過ぎましたが、何本かはもう少しゆっくりと通過した。

these drew up at the station close by, and sometimes made an awful shriek and groan before they stopped.

これらはすぐ近くの駅で停車する汽車で、停車する前に恐ろしい[ひどい]キーッときしむ音を上げ、うなり声を立てることもあった。

I thought it very dreadful, but the cows went on eating very quietly,

僕はそれを非常に恐ろしいと思ったが、牛たちはとても落ち着いて[静かに]食べ続け、

and hardly raised their heads as the black frightful thing came puffing and grinding past.

黒く恐ろしいものが(煙突から煙を)ポッポッと立ちのぼらせやってきて、ギーギー音をたてて通り過ぎていっても、ほとんど頭をあげませんでした。

For the first few days I could not feed in peace;

最初の数日間、僕は安心して食事をする[餌を食う]ことすらできなかった。

but as I found that this terrible creature never came into the field, or did me any harm,

しかし、この恐ろしい生き物が決して畑に入ってこないことや、害を加えないことが分かったので、

I began to disregard it, and very soon I cared as little about the passing of a train as the cows and sheep did.

私はそれを無視するようになり、すぐに牛や羊のように列車が通ることを気にしなくなった。

Since then I have seen many horses much alarmed and restive at the sight or sound of a steam engine;

それ以来、僕は、蒸気機関車の姿を見たり、音を聞いて非常に驚いて、暴れ出す[そわそわした・進むのをいやがる]多くの馬を見てきた。

but thanks to my good master’s care, I am as fearless at railway stations as in my own stable.

しかし、親切なご主人様の気配りのおかげで、私は自分の厩舎にいるときと同じように、鉄道の駅でも恐れることはなかった。[恐れを知らない]

Now if any one wants to break in a young horse well, that is the way.

さて、だれかが若い馬をうまく調教【する】したいと思うなら、このようにすることだ。[これがその方法だ]

My master often drove me in double harness with my mother, because she was steady and could teach me how to go better than a strange horse.

ご主人様はよく僕をママと一緒に二頭立てで走らせた。なぜなら、ママは安定していて、知らない馬よりも上手に、走り方を教えることができたからだ。

She told me the better I behaved the better I should be treated, and that it was wisest always to do my best to please my master;

ママは、僕が行儀よくすればするほど良い扱いを受けることができ、ご主人様を喜ばせるためにいつも最善を尽くすのが一番賢明だと言った。

“but,” said she, “there are a great many kinds of men;

「でもね」 と彼女は言った。 「とてもたくさんの種類の人間がいるのよ。

there are good thoughtful men like our master, that any horse may be proud to serve;

私たちのご主人様のように善良で思いやり深い人間なら、どんな馬でも喜んで仕えるでしょう。

and there are bad, cruel men, who never ought to have a horse or dog to call their own.

ですが、馬や犬を自分のものとして飼うべきではない、(素行の)悪い、残酷な男たちもいます。

Besides, there are a great many foolish men, vain, ignorant, and careless, who never trouble themselves to think;

その他にも、うぬぼれが強く、無知で、不注意で、自分で考えようとしない、愚かな人がたくさんいます。[trouble oneself わざわざ~する]

these spoil more horses than all, just for want of sense; they don’t mean it, but they do it for all that.

こんな人たちは、思慮[判断能力・分別]が足りないから、誰よりも[とりわけ]、たくさんの馬を台なしにしてしまいます。彼らにはそのつもりはなくても、それにもかかわらず、そうしてしまうのです。

I hope you will fall into good hands;

良い人の手に渡る[ある立場・状態に置かれる]といいわね。

but a horse never knows who may buy him, or who may drive him;

しかし馬には誰に買われ、誰に乗り回されるかを知ることはできません。

it is all a chance for us; but still I say, do your best wherever it is, and keep up your good name.”

すべて運なの。それでも、どこであろうとベストを尽くし、名声を汚さないようにしておくれ」 [維持する]