※カラフル対訳で紹介している作品はすべてパブリックドメインです。

このサイトで使われている作品のすべては著作権の切れた名作などの全文を電子化して、インターネット上で公開しているProject Gutenberg(プロジェクト・グーテンベルク)、LibriVox(リブリヴォックス、朗読図書館)の作品を出典としています。

翻訳者:中務秀典

名作『宝島』で英語が楽しく学べる!

His stories were what frightened people worst of all.

やつの話はなによりも[どんな悪いことより]みんなを怖がらせた。

Dreadful stories they were–about hanging, and walking the plank,

それは恐ろしい話ばかりで、縛り首や、板歩きの刑、[目隠しした捕虜を板の上で歩かせ、海に落とす]

and storms at sea, and the Dry Tortugas, and wild deeds[行為, 行動] and places[場所,環境] on the Spanish Main.

あるいは海の嵐や、ドライトルトゥーガス諸島に関すること、カリブ海での狼藉やその風土についての話だった。

By his own account he must have lived his life among some of the wickedest men that God ever allowed upon the sea,

やつ(自身)の説明では、自分こそは神が海に生を許した最も邪悪な者たちの中で生きてきた男に違いないとのことで、

and the language in which he told these stories shocked our plain country people

そして、やつのそんな話をするときの言葉遣いは、僕ら平凡な田舎の人々には衝撃を与えた。

almost as much as the crimes that he described.

奴が話す犯罪とほとんど同じくらいに(衝撃を与えた)

My father was always saying the inn would be ruined, [破滅する]

僕の父はいつもこの宿はつぶれるだろうと言っていた。

for people would soon cease coming there to be tyrannized over[虐げる] and put down, and sent shivering to their beds;

虐待されたりやりこめられたりして、震えながらベッドに逃げ込まされるようでは、宿泊客たちは、すぐに宿に来るのをやめてしまうだろうと思ったんだ。

but I really believe his presence did us good.

でも僕は、やつの存在は良かったんだと思っている。

People were frightened at the time, but on looking back they rather liked it;

みんなそのときはおびえていたけど、振り返ってみるとむしろそれを楽しんでいたんだ。

it was a fine excitement in a quiet country life,

静かで平凡な田舎暮らしのなかでは、いい刺激になり、

and there was even a party[一隊] of the younger men who pretended to[~するふりをする] admire him,

若者の中にはやつを尊敬しようとするようなものたちまでいて、

calling him a “true sea-dog” and a “real old salt” and such like names,

やつを『本物の老練な船乗り』とか『正真正銘の老練水夫』とかそんな名前で呼んで、

and saying there was the sort of man that made England terrible at sea.

イギリスを海で恐れさせたのはああいった男だと言っていた。

In one way, indeed, he bade[宣言する] fair to ruin us, for he kept on staying week after week, and at last month after month,

実際にある意味では、やつは僕らをほんとうに破滅させそうだった。やつは何週間も、しまいには何ヶ月にもおよび宿泊して、

so that all the money had been long exhausted[使い尽くされた], and still my father never plucked up the heart to insist on having more.

だから、金はとっくに使い果たしてしまっていたんだけど、それでも僕の父はもっとお金を払ってくれと勇気を奮って言い張るなんてできなかった。

If ever he mentioned[言及する] it, the captain blew through his nose so loudly that you might say he roared,

もし父がお金のことを話したとしたら、きっとキャプテンはまるで獣が吠えるみたいに大きく鼻を鳴らし、

and stared my poor father out of the room.

僕のかわいそうな父をにらみつけて部屋から追い出してしまっただろう。

I have seen him wringing his hands after such a rebuff,

僕は父がそんなふうに拒絶されたあと、両手を握り締めているのを見たことがあり、

and I am sure the annoyance and the terror he lived in[恐怖の日々] must have greatly hastened his early and unhappy death.

そんなふうに苛立ち怯えた生活が、父の死期を大いに早め、不幸ななものにしたに違いないと思う。

All the time he lived with us the captain made no change whatever in his dress

僕たちと一緒に暮らしている間ずっと、キャプテンは着ているものをまったく変えなかった。

but to buy some stockings from a hawker.

行商人から靴下を何足か買った以外は。

One of the cocks of his hat having fallen down, he let it hang from that day forth,

帽子の縁の上そりの片側が倒れて下がってしまっても、倒れた日からずっと垂らしたままだった。

though it was a great annoyance when it blew.

風に吹かれて動いたらすごく鬱陶しいだろうに。

I remember the appearance of his coat, which he patched himself upstairs in his room,

僕は、やつのコートの(ぼろぼろの)体裁を覚えてる。二階の自分の部屋でつぎはぎをして、

and which, before the end, was nothing but patches.

最後の頃にはつぎはぎの布のみになってしまっていた。

He never wrote or received a letter, and he never spoke with any but the neighbours,

やつは手紙を書いたり受け取ったりすることもなく、近くのもの以外と話すこともなかった。

and with these[speak with these], for the most part, only when drunk on rum.

その近所のものと話すときでさえ、たいていはラムで酔っ払ったときだけだった。

The great sea-chest none of us had ever seen open.

誰も、あの大きな衣装箱が開いているのを見たことはなかった。

He was only once crossed, and that was towards the end, when my poor father was far gone in a decline that took him off.[父の命を奪う病]

やつは一度だけ他人にやり込められたことがあって、それは晩年の、かわいそうに父の死の病もだいぶん進行して衰退の一途をたどっていたころだった。

Dr. Livesey came late one afternoon to see the patient, took a bit of dinner from my mother,

リバシー先生がある日の午後遅く患者を診察するためにやってきて、母が用意したちょっとした夕食をとり、

and went into the parlour to smoke a pipe until his horse should come down from the hamlet,

馬が村からやってくるまでの間、リバシー先生は客間へ入ってパイプをふかしていた。

for we had no stabling at the old Benbow.

ベンボウ亭は古くて馬屋の設備がなかったので

I followed him in, and I remember observing[観測する] the contrast

僕もリバシー先生のあとについて(食堂に)入っていき、対照的な違いに気づいたことを覚えている。

the neat, bright doctor, with his powder as white as snow and his bright, black eyes and pleasant manners,

こぎれいで明るく、髪には雪のように真っ白な粉をふり、目は黒く輝いていて、行儀が良く感じのいい態度は(対照的な違いをひきたてた)

made with the coltish country folk, and above all, with that filthy, heavy, bleared scarecrow of a pirate of ours,

きままな田舎者たち、とりわけ不潔で重苦しく、目をとろんとさせたかかしのような、僕らのあの海賊、

sitting, far gone in rum, with his arms on the table.

そいつは、テーブルに両腕を投げ出して座り、ラムでひどく酔って(目をとろんとさせていた)

Suddenly he–the captain, that is–began to pipe up his eternal[お決まりの] song:

とつぜんやつ、キャプテンがいつもの歌を(突然)歌いはじめた。

Fifteen men on the dead man’s chest–Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!

死んだ男の衣装箱に15人の男が…ヨーホー!ヨーホー!ヨーホー! ラム酒が1本!

Drink and the devil had done for the rest–Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!

あとのやつらは酒に飲まれ、悪魔にやられた。ヨーホー!ヨーホー! ラム酒が1本!

At first I had supposed “the dead man’s chest” to be that identical big box of his upstairs in the front room,

僕は最初のうち、『死んだやつの衣装箱』とは二階表側の部屋においてあるあの大きな箱(そのもの・同一の)のことだと思っていたから、

and the thought had been mingled in my nightmares with that of the one-legged seafaring man.

その考えは僕の悪夢の中で、あの片足の船乗りの男の話と混ざり合っていたのだった。

But by this time we had all long ceased to pay any particular notice to the song;

でもこのころにはもう、僕たちはとっくにその歌に特別な注意を払うのをやめていた。

it was new, that night, to nobody but Dr. Livesey, and on him I observed [観察する] it did not produce[引き起こす] an agreeable effect,[感じのよい印象]

その夜、初めて聴くのはリバシー先生だけだったが、僕(が観察する)には、先生があまり快く思っていないように思えた。

for he looked up for a moment quite angrily

というのも、先生はしばらくとても怒って上を見上げていたからだ。

before he went on with his talk to old Taylor, the gardener, on a new cure for the rheumatics.

老庭師のテーラーさんとリューマチの新しい治療法について話しはじめる前に、(怒ったように上を見上げていた)

In the meantime, the captain gradually brightened up[顔などが輝く] at his own music,

そうしているうちに、キャプテンは自分の歌声にだんだん昂奮してきて、

and at last flapped his hand upon the table before him in a way[という方法] we all knew to mean silence.

そしてとうとう、みんなが知っている『静かにしろ』という意味で、目の前のテーブルを手のひらで叩きつけた。

The voices stopped at once, all but Dr. Livesey’s;

リバシー先生を除いて、みんなの声はすぐにやんだ。

he went on[態度をとり続ける] as before speaking clear and kind and drawing[吸う] briskly[活発に] at his pipe between every word or two.

リバシー先生は、変わらず明瞭な優しい声で話しつづけ、一言二言しゃべってはパイプを短くすぱすぱふかした。

The captain glared at him for a while, flapped his hand again, glared still harder,

キャプテンはしばらくリバシー先生を睨みつけ、もう一度テーブルを叩き、さらに鋭く睨みつけた。

and at last broke out with a villainous, low oath[低いののしり声], Silence, there, between decks! Were you addressing me, sir? says the doctor;

そしてついに口を開くと、悪辣な低い声でののしった。「黙れ! おい、おまえら!」「私のことかね?」ドクターがそう尋ねると、

and when the ruffian had told him, with another oath, that this was so,

そのごろつきが、またののしりながら。ああ、そうだと言うと、

I have only one thing to say to you, sir, replies the doctor,

お前に言っておくことはひとつだけだ、と先生は答えた。

that if you keep on drinking rum, the world will soon be quit of[~が去る] a very dirty scoundrel!

「 もしラムを飲みつづけるなら、もうすぐこの世からとても薄汚れたならず者が一人いなくなることになるとな!」

The old fellow’s fury was awful.

老人の怒りはすさまじかった。

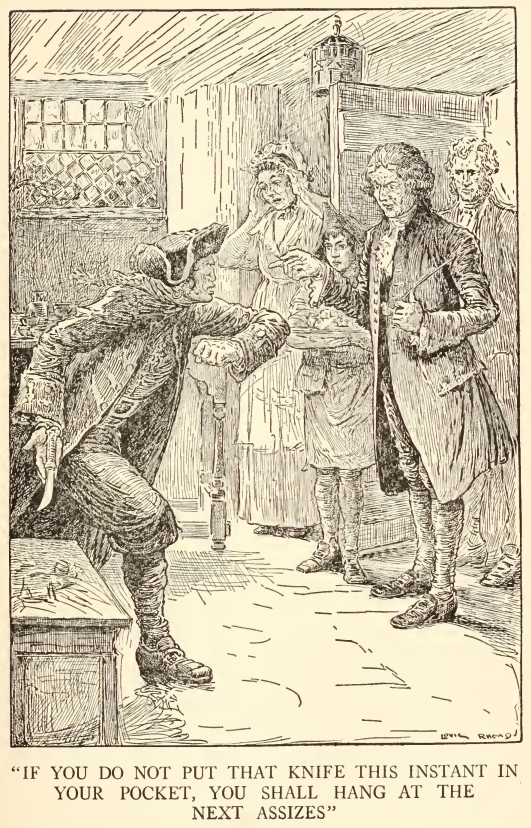

He sprang to his feet, drew and opened a sailor’s clasp-knife,

やつはとびあがり、船乗りの折りたたみナイフを抜いて開くと、

and balancing[バランスをとり] it open on the palm of his hand, threatened to pin the doctor to the wall.

手のひらを開いてナイフを転がし、壁にはりつけにするぞと脅した。

The doctor never so much as moved.

ドクターは身じろぎひとつしなかった。

He spoke to him as before, over his shoulder and in the same tone of voice,

それまでどおり、肩越しに同じ調子でやつに話しかけた。

rather high, so that all the room might hear, but perfectly calm and steady:

その部屋全体に聞こえるように多少高い声だったかもしれないが、落ちつき払って平然として(やつに話しかけた)

If you do not put[置く] that knife this instant[この瞬間に] in your pocket, I promise, upon my honour, you shall hang[首をつってぶら下がっている] at the next assizes.

「今すぐにそのナイフをポケットにしまわないなら、私の名誉にかけて誓ってもいいが、お前は次の巡回裁判で絞首刑になってるだろう」

Then followed a battle of looks between them, but the captain soon knuckled under, put up[を納める] his weapon,

それから二人の間で睨み合いが続いたが、まもなくキャプテンが降参して、凶器をしまい、

and resumed[再び続ける] his seat, grumbling like a beaten dog.

負け犬のようにぶつぶつ不平を言いながら、ふたたび席に戻った。

And now, sir, continued the doctor, since I now know there’s such a fellow in my district,

「いいかい」ドクターは続けた。「私の地区にお前のようなやつがいたと知ったからには、

you may count[みなす] I’ll have an eye upon you day and night.

昼も夜も私がおまえさんを見張っていると思うがいい。

I’m not a doctor only; I’m a magistrate;

私は医者であるだけでなく、治安判事でもあるんだ。

and if I catch a breath of complaint against you, if it’s only for a piece of incivility like tonight’s,

もしおまえに対するほんのわずかな苦情でも耳にしたら、今夜みたいな無礼な行為ひとつであっても、

I’ll take effectual[有効な, 効果的な] means to have you hunted down and routed out[引きずり出す] of this. Let that suffice.[let it suffice to say]

私がすぐにしかるべき手段を講じて、おまえを追いつめ捕えてここから追放だ。言いたいことはそれだけだ」

” Soon after, Dr. Livesey’s horse came to the door and he rode away, but the captain held his peace[平和を保っていた] that evening, and for many evenings to come.

まもなくリバシー先生の馬がドアのところにやってきて、ドクターは馬に乗って去っていった。でもキャプテンはその晩も、それからしばらくも静かなものだった。